We last spoke to guitarist extraordinaire Guthrie Govan at the NAMM 2009 Show in Anaheim, California. Throughout the past year Guthrie’s kept quite busy with a variety of musical endeavors, all while continuing to gain widespread recognition both inside and outside of the guitar community.

We last spoke to guitarist extraordinaire Guthrie Govan at the NAMM 2009 Show in Anaheim, California. Throughout the past year Guthrie’s kept quite busy with a variety of musical endeavors, all while continuing to gain widespread recognition both inside and outside of the guitar community.

In early 2010 Guthrie embarked on an East Coast clinic and concert tour, including a stop at Berklee College of Music in Boston, Massachusetts, where we took advantage of the opportunity to catch up and learn more about what he has been up to:

IC: Can you fill us in on what you’ve been up to this past year?

GG: Mostly, my life over the last year has been a series of exciting things that have conspired to stop me from making the next album. So to answer the next question – I can just sense it: there is still no next album. This is the year where I’m going to make it happen. I’m gonna carve out a big chunk of calendar and say no to everything else.

IC: I’m pretty sure that was the second question last time we talked – it was a pretty similar answer, too… [laughs]

GG: Some crazy things have got in the way – some stuff cropped up in my career that I couldn’t really turn down.

IC: Sounds like that’s a good thing.

GG: Yeah. Most notably – and I think we talked about this last time – the fact I do a lot of sample replays for the guys in the dance community who’ll demo some house track using four bars of some famous recording, and then discover that they can’t use that sample once the record company releases the tracks. I work for this company that sometimes just copies the loop note-for-note – which apparently is legally a different situation, even though it tends to end up sounding identical. Sometimes we have to rewrite things, like write a pastiche of this song in the same key and tempo.

We never know who the client is going to be, so we have to try and make sure they’re all good, and every now and then somewhere down the line we discover we’ve played on an album that’s at the top of the charts in the UK – which happened most recently with a guy called Dizzee Rascal, who’s maybe not a household name over here, but he’s the rapper in the UK.

The exciting offshoot of all of this is that once we discovered we’d accidentally played on his album, a couple of months later the BBC, which is the big government-funded broadcasting company in England, approached Dizzee – every year they do a thing called the Electric Proms, where they’ll take some big popular artist and put them together with an orchestra or a choir or something surreal like that, so you get to see these famous songs being played in the wrong context altogether. It makes for quite interesting viewing.

They stuck Oasis in a big room with some philharmonic orchestra last year, and this year they said to Dizzee: ‘Would you want to do something? We’ve got a male voice choir for you, we’ve got a string section for you – do you think you could put a band together?” And what’s he going to do? In the world of rap, you generally go onstage with your friend who has a turntable, you shout ‘Yo!’ a little bit, and people come just to see the rapper, so he didn’t really know how to put a band together.

| [flashvideo file=”https://guitarmessenger.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/gginterview.flv” width=430 height=273 image=”https://guitarmessenger.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/video.jpg” /] |

What are you going to do? You call the people who accidentally played on your album. So, we ended up on British TV with a giant, giant band – a 20-piece string section, a 13-piece rock band with horns and all that, and it went so well that he decided that he wanted to do that for all the big live gigs.

IC: So did you end up going on tour with him?

GG: Kind of. It’s not like a regular tour, where you can say: ‘Alright, I’ll block out April. April is going to be 20-something gigs.’ We only get the good gigs, which is flattering, but also leaves you with a pockmarked diary – festival here, festival there. But it’s all going well, and we’re excited to be doing something like that. It’s not what the guitar heads would expect me to do, but it is a lot of fun. I think it’s cool, because a rapper is doing something that most rappers don’t do, and embracing our chosen field. And if you can play to that kind of audience, it means new people are going to see what you can do with a rock band, and what an electric guitar actually sounds like these days. It’s all very fruitful. The days of real-instrument people over here and dance people over there scowling at each other – that has got to stop. Neither faction is going anywhere anytime soon, so we might as well make friends and cross-pollinate.

IC: I’m sure it will yield some interesting results, too. So since I can’t ask you when the new album is coming out, maybe I can ask if there’s anything you can share with us as far as the direction of the writing. Have you done any of the writing for it, and how does it compare to Erotic Cakes?

GG: None. I’ve done no writing for it at all. I’ve got tunes – there is a big pile of stuff. I could assemble the album starting tomorrow, I’ve got enough material, but I don’t want to do that – because Erotic Cakes was something that took so many years to develop. There’s tunes on there that I wrote at the end of the 80’s or the start of the 90’s. It spans this whole chunk of a third of my life. So I want the next album to be entirely the opposite – where the whole thing is conceived and written and recorded and mixed and the whole process will happen in a short period of time, and it’s just a snapshot of life. I kind of insist on wanting to do it that way, just so I learn what that feels like and what’s different compared to the way I did the last one.

Also, I’ve discovered that when you make an album, you tend to end up spending the next 18 months or so doing clinics and playing with an iPod – playing the same songs over and over again. And they’re unflinching backing tracks, they never change, there’s no live interplay, and that’s just the way a lot of guitar gigs have to be. So I want the stuff to be as fresh as possible, and to excite me as much as possible, so that I don’t get tired of it so quickly. You can imagine how I feel about something like ‘Fives’ now – I never want to hear it again, certainly not in its backing-track incarnation.

IC: An interesting move about Erotic Cakes that happened, that we didn’t discuss last time, was the fact that it came out on Cornford Records. It’s something a little different to have your album released by what is primarily an amp company. Could you talk about your relationship with Paul Cornford and how that came together?

GG: It was more of a gentleman’s agreement than a real business agreement – no one ever signed anything. But the thing with me and Paul – I’ve used the amps for ten years, and again, never signed anything. It’s all based on mutual respect – he seems to like what I do, I love what he does. So we try and help each other out. With regard to the album, the album only happened because Paul said: ‘I’ve had enough of this situation where you don’t have an album out.’ And I came up with various excuses for not having one out: ‘I don’t think there’s a market for it, I can’t afford to record…’ He said: ‘Look, we’re going to do an album. I’ll fund for it. All you have to do is turn up somewhere and play what’s instructed.’

So he made sure the album got finished, and made sure it sounded good. He took things a lot more seriously than you’d expect [him to do for something that’s of small concern to him] – things like getting a really good guy to mix the album, recording the guitars properly in a big studio – things that I think a lot of guitar albums now don’t have. There’s such a pressure to try and do as much of it as you can on your own computer with your own trusty Pod or whatever, and make it a low-budget recording on the assumption than no one’s going to buy it anyway. But Paul’s vision was a little bit more ambitious. He said: ‘Let’s make sure this is a hi-fi buff’s kind of album, and it actually sounds good on a decent system.’

IC: I agree. That’s a fresh breath of air in the guitar community, too. I wonder how many records we would have listened to and perceived differently had they been recorded with a band, recorded with a real rig, and mixed properly.

GG: I like the fact that if you look at it that way, you’re treating it as music, rather than just a vehicle for counting the notes. Like: ‘Here’s 70 minutes worth of licks you might want to slow down and steal.’ I think that’s so counterproductive. It feels so much better if you can come up with something and say: ‘Well, that’s proper music. Someone who doesn’t play my instrument might enjoy some of this.’ I think that’s a good goal.

IC: While we’re on the subject of Cornford – can you tell me a little bit more about your amps, and what it is that you look for in an amp? You have a distinct sound.

GG: This will sound a bit dating agency, but what I look for in an amp is honesty [laughs]. To me, an amplifier should just amplify – as in, whatever you feed into it, it should make it louder and give it back to you. The kind of amp I shy away from is the one that tries to force too much of its own character on what you’re playing.

There are certain amps that flatter a certain kind of playing, but have a tendency to homogenize the various players who can plug into it. I don’t trust an amp where you can plug a Tele in or a Les Paul in, or get ten different people to play the same guitar through it, and it all sounds pretty much the same – even if it’s a nice sound. I feel hampered by that.

I like the warts and all to come back through the speaker cab – any imperfections, all the variations in the way you hit a string. I think that’s what my playing’s all about – more than circus tricks, the fact that every note can be unique. If I give the same guitar to someone else and say: ‘Alright, now you play that scale.’ it will sound different. Cornfords are really good for that, and really unforgiving. For someone who’s used to shredding away at bedroom levels with really high gain, they plug into a Cornford and they’re generally horrified.

IC: You mentioned articulation, and that’s something I actually wanted to talk about. Articulations and inflections are certainly some of your strengths – you’re able to take the same gear without changing anything and get a bunch of different sounds just by the way you pick, the way you attack. Did you specifically spend time figuring out those sounds?

GG: It’s not something I ever figured out in as much detail as I now talk about it at clinics. To me, being raised on blues and blues-rock and all that stuff, articulation and attack and the individuality in each note – that’s what it’s all about. There’s like three licks that you play, and everything else is about the way that you tell them. It’s the tone, it’s the variation from one note to the next. So to me, as a kid learning how to play all those blues-rock things, it seemed so obvious to me that that’s the point – that’s what you’re supposed to do. You’re supposed to worry more about how you hit the note, and what the note sounds like than even what the note is.

Now that I seem to be moving more in circles where the people who come to see me often have Dream Theater T-shirts, and they like the odd time signatures and the too many notes per second and that side of what I do, to a lot of them it seems like it’s a revelation when I talk about this stuff: ‘Did you know that you can play a note three times in a row with the same amp and the same volume control settings and make it sound different?’ ‘Really?’ I’m sort of this evangelist for the obvious. There are different extremes in the spectrum of guitar players – there are people that are really good at the nuance thing and maybe they shy away from the more complicated stuff, and if someone’s absorbed by the terrifying Prog side of things, sometimes they won’t bother with the bluesy inflection aspect – because they think there’s no need for it.

But yeah, it’s just something I’ve always done. I’ve always cared about that stuff. I remember as a kid being fascinated by the way B.B. King, Albert King, and Freddie King could all play the same note, and I’d know which King it was. I was like: ‘How do they do that?’

IC: Something from [yesterday’s] clinic, that I would like to hear your thoughts on again for the interview, is your approach to time – I think you’re very aware of when you lay back on the beat and when you’re pushing it for a certain effect. Can you talk about how you work on that, or if you work on that at all?

GG: It’s a bit like the articulation thing. It’s not something I work on, per se – it’s just something you should always be aware of every time you play a note. Part of your duty to that note is to put it somewhere where it feels good, because somebody out there is expected to listen to it. I think even people who don’t play guitar will start to feel a little bit uncomfortable and turned off by what you’re doing if you do that classic ‘rushing the notes’ thing. It’s something I see a lot when you see someone who’s just learned how to play something new – there’s a certain tension, a certain fear of failure when they’re trying to play it and they haven’t quite nailed it yet. The natural thing to do, perversely, is to rush it and play it slightly faster than you need to.

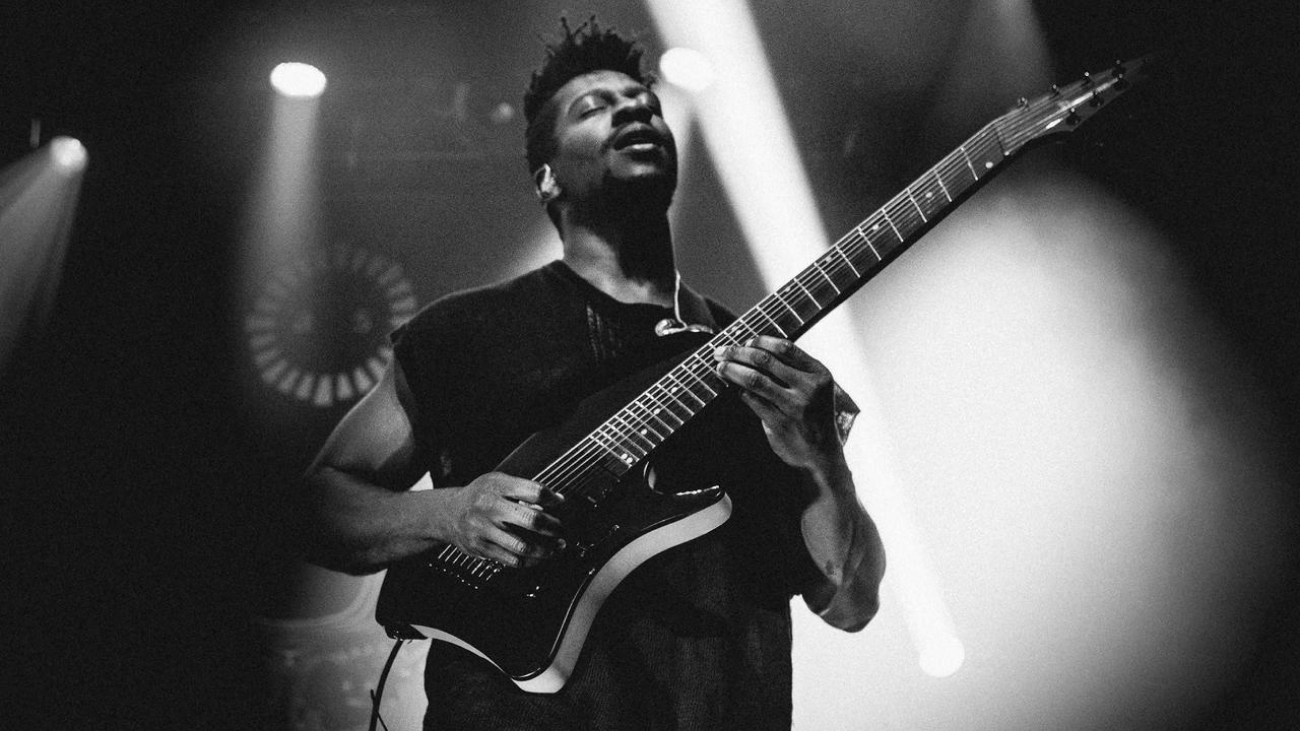

Guthrie Govan with Berklee professor Jon Finn

I think relaxing is generally the best thing you can do. If everyone in the band has to play some event or another on beat one, I think the coolest thing you can do is be the last guy playing on that beat. I think yesterday I was probably rambling on about rappers and Miles Davis, and all of these people who sound so cool because they’re not in any hurry to play the note. Being metronomically in time is great and has its place, and I think playing late has its place, but rushing stuff doesn’t do it for me.

Again, it’s the kind of thing that’s so obvious when you listen to music. When you turn off musician mode and just become a consumer of music, this stuff is just instinctive and you can sense it – you know whether it feels good or not. But as soon as you’re at the steering wheel with the instrument, different rules seem to apply. So I try to encourage people to be a member of the audience and listen to what they’re doing as they do it, and that irons out a lot of the problems.

IC: What do you consider personally to be your strengths and weaknesses as a musician and guitar player? I think we all have things that we’re always working on and trying to get better at… you have a lot less of those things than most of us [laughs].

GG: Everyone has stuff that they could be working on. I think about a player like Carl Verheyen – I’ve done teaching things with him, and he’s a ridiculous encyclopedia of stuff. There is a guy who doesn’t need to learn any new chord shapes or any new licks – he’s got all of them already. But every day of his life, he’ll sit down and learn a new lick or write a new chord shape or further himself in some way. I don’t think it ever stops.

Strengths and weaknesses, you say? I guess I’ve got a good ear, because I learned that way. I like to think I’m fairly good at just inventing music up there [points to head] as an abstract thing, and then knowing how to play it. The improvised field of music is probably where I feel the most comfortable – I don’t know if that makes it a strength or if that’s a laziness thing, or what it is.

I could be more disciplined. Probably the biggest weakness I can think of is: if I’m sitting there in a studio trying to come up with a guitar part or a bass line or something like that – I don’t know when to stop. I always get distracted by new things, though it’s sort of fun to have that childlike thing: ‘I wonder what else we could do?’ But in terms of actually spending studio time efficiently, coming up with a part, remembering what a part is and just playing that – that’s not a selling point, really.

IC: Looking back on your career, is there anything you would have done differently as far as your development, both on the playing side and the career side?

GG: I don’t know. I don’t think it’s necessarily that helpful to look back and think what you could have done differently. All you can do is learn from what you have done and then proceed. You can’t change anything from the past – you can learn from it, but don’t regret it. Arguably, I could have made an album like Erotic Cakes a good decade earlier, but there’s something cool about not having done that.

When that album did come out, it was quite an interesting time for guitar playing. It seemed like people were surprisingly receptive to that kind of playing, and of course you’ve got the internet there and all of this strange, underground mysterious marketing that kind of does itself – none of which would have happened ten years before. I think I would have sold more copies, because it was harder to steal music en masse a decade earlier. But in terms of getting the word out, and stuff like that…

IC: I think for some people it reestablished your spot on the map once the album came out, and I think a lot of people in the guitar community found out about you for the first time when the album dropped.

Guthrie Govan and Ivan Chopik

GG: I hope so. I meet people sometimes in really strange places like airports, and somebody will say: ‘Hi, I’m from Saudi Arabia – we love you there!’ Which is very surreal, but then they’ll go on to say: ‘We love your YouTube clips where you play blues too fast. You should join a band.’ Or they’ll say: ‘You should make an album.’ And it’s like: ‘The Internet has other things apart from YouTube – there’s this great thing called Google. You should investigate it, because actually I did make an album, I’m in a number of bands…’

So it’s a start. It gets the name out, but you can’t always trust people to carry on and do the rest of the research to find out more about this person they’ve discovered.

IC: That’s certainly true of that YouTube clip of you playing one bar each of different players. I think that was for Guitar Techniques magazine.

GG: It was. Thank you for knowing that. I think some people have watched that, and they assume that’s what I consider a good use of my time: ‘Let’s write a song where it’s like three beats of B.B. King, two bars of Zakk Wylde…’ It’s totally pointless, really – it’s a little bit of a circus trick. It was a bit of fun in the magazine context, but when someone posts it illegally without explaining what it is…

IC: What do you see as some of the big things happening for you in the near future?

GG: There’s one thing I’m quite excited about – I got a phone call just before I came out to the U.S. from Lee Ritenour. Lee – man of fusion, wonderful player, got in touch with me and said: ‘I’ve got this project that I’m working on called Six String Theory, and we’re going to have different guitar players on every track.’ And I’m like: ‘Okay, here we go. It’s one of these things again.’ And then he told me who the guitar players were: Steve Lukather, Neal Schon, B.B. King, George Benson, Mike Stern, John Scofield, Joe Bonamassa – and for reasons I can’t even pretend to understand, me. I think Lee’s son had heard me on YouTube, oddly enough. He hangs out with Kenny G’s son, who’s a big Opeth fan [laughs].

So we did a rerecording of ‘Fives’ – my favorite – and I actually like ‘Fives’ again, because the backing band was Larry Goldings on Hammond, Tal Wilkenfeld on bass, and Vinnie ‘God’ Colaiuta on drums. I’m like: ‘I can’t believe I’m playing with these guys.’ They injected something new into that track, so I’m intrigued to see what happens when that comes out.